Women’s Bodies and Horror: Teaching Carmen Maria Machado’s Her Body and Other Parties

Our class has been discussing Carmen Maria Machado’s short story collection, Her Body and Other Parties. This is a book that I’m deeply invested in, not only because of its beautiful writing but because it’s one I’m incorporating into my own work. I’ve been thinking with this book for some time, but returning to this book now has been particularly special. Since the outbreak of the pandemic, I’ve been thinking a lot about Machado’s short story, “Inventory,” in which a woman navigates her way through the U.S. to end-up on an island off the coast of Maine, alone. She is escaping a pandemic herself, one that, importantly, is transmitted through human contact. Meeting an ex-CDC employee, she is told that “the fucking thing is only passed through physical contact […] If people would just stay apart––” How apropos for the time we’re living in and the pandemic we continue to experience.

As the narrator of “Inventory” understands, the desire for human contact is so profound that it cannot be avoided. We put ourselves in danger, we betray ourselves (?) in order to feel another body close to ours. In the most difficult moments, touch, comfort, care is what we need most. But, what happens when, like our narrator, we are alone? This is the most horrific possibility the story itself presents.

I assigned this collection for our Latinx monsters class because of the innovative ways Machado implements the tropes of speculative fiction and horror in order to represent women, and in particular their bodies. Right before Boston implemented its “shelter in place” order, I also participated in a roundtable at NeMLA 2020 that centered on Machado and her work. The primary concern of the roundtable was examining her work as a turn in Latinx literary studies. Our roundtable considered the Latinxness of her text, where no overt markers of race or ethnicity are evident, and I’m interested in asking my students whether they considered Her Body andOther Parties a Latinx book and why.

As I stated in my NeMLA paper, Latinx scholars have demonstrated an affective attachment in reading Machado as a Latinx author, although her work evinces no overt signs of race and ethnicity (either Latinx or white). While she is technically a Latinx author, Her Body and Other Parties makes no reference to race or ethnicity. Resorting to lyrical “high art” literary language––MFA pedigree and training is evident here––the text allows all characters to “pass” (of course, this is a larger claim about our reading practices which see all characters not clearly identified racially or ethnically as “white”). Imaging Machado’s work as Latinx positions latinidad as a speculative endeavor that is outside the reach of language—unsayable and unknowable.

My paper focused on a comparative analysis of Machado alongside Han Kang’s novel, The Vegetarian. This examination of the speculative female body unearths unexpected yet interrelated narrative strategies, literary patterns, and networks; networks that are particularly significant in our contemporary moment in which difficult conversations of sexual abuse and its intersection with race, ethnicity, financial, and institutional power have dominated our zeitgeist.

The central questions that organize this work are: How do I consider my body? Where do I find its beauty? Where do I find its pleasure? How does the world demand I consider it and how do I make space for it within the world? I have been thinking a lot about a couple lines from a Muriel Rukeyser poem, “Käthe Kollowitz,”: “What would happen if one woman told the truth about/ her life?/ The world would split open.” Indeed, representations of the female body, sexuality, and desire in Machado and Kang rip apart not only the world, but the body, and the text itself. In centralizing the experiences and desires of women in their texts, Machado and Kang obliterate expectations of fiction—for linearity, wholeness, and resolution—while also inflicting pain on the self. The high literary style of both writers also associates this violence and self-abnegation to notions of aesthetic pleasure and artistic merit.

Machado’s short story collection is, as the title suggests, deeply concerned with female embodiment—its shape and size. It is also interested in food and eating, especially as it affects the female body. Kang’s novel, as its title suggests, is also concerned with eating, or, more precisely with its inverse, abstention—denial and rejection of the human body. Food, eating, the body: what should be sources of pleasure are instead ones of discomfort, pain, denial. Forbidding yourself of food so the scale reads 105 instead of 106, watching your hip bones jaggedly display themselves, a source of pride in their accomplishment. Delight in seeing how far you can push your body, delight in its pain. How far can I go? How small can I make myself? Seeing the least amount of space you can take—do I want to become invisible? How much pain can it endure? It, not I—a separation of body from self. How much pleasure can I achieve from its pain? Or, the pleasure in overindulgence, seeing how much you can take in, put away. How much can my flesh expand? How many layers can it take? How much space can my body demand?

In my work, I consider how both texts foreground the female body as a speculative arena through which self-abnegation and refusal are explored in relation to eating, hunger, and desire. The body acts as the space through which colonial and racial violences are explored and through which women enact their resistance and defiance against systemic patriarchal domination. However, resistance takes place not, as expected, through typical acts of dissent, but through forms of refusal and self-abnegation that hurts the self.

The women of Her Body and Other Parties enact a shadow feminism that manifests itself through forms of self-destruction, masochism, and a refusal of the typical bonds that would define us as women. In many ways, these women refuse to reproduce their relationship to patriarchal forms of power, yet in so doing hurt themselves, and at times, self-destruct. In a world that continually performs violence on the body of the female subject, why not refuse to eat meat and then food altogether? Why not become plant? Why not assume control over your own destruction? Why not become dress-ghost? Why not untie your ribbon and let your head drop to your husband’s feet? In Her Body and Other Parties we see a version of woman that is messy, porous, violent, self-loathing; one who refuses to remake and rebuild. The women of Machado’s narratives “seeks instead to be out of time altogether, a body suspended in time, place, and desire” (Halberstam 145).

Machado’s short story collection is concerned with many female-centered subjects: queer love, queer sex, sexual and gendered violence, the reimagination of fairy tales, motherhood and procreation. It is also deeply concerned with corporeality, female embodiment, eating, and fatness. Throughout eight short stories Machado lyrically tells various narratives that center women and their desires, the violence they endure and survive, and the systemic forms of cruelty and oppression women are always subject to—all in speculative and fantastical modes. The stories I will focus on here are also particularly interested in the female body, its weight, visibility, and undoing. “The Husband Stitch,” for example, reimagines the classic fairy tale, “The Green Ribbon,” which tells of a young girl with a green ribbon around her neck who refuses to tell her boyfriend-then-husband why she wears it. In their old-age, however, she allows her husband to untie the ribbon, causing her head to fall off. Machado’s reimagination centralizes male psycho-sexual desire and power over women and the passing-on of this power generationally. Ultimately, the text asks us to consider who has the power to undo and unbecome. The title of the story, it should be noted, is a reference to a purported surgical procedure in which one or more sutures than necessary are used to repair a woman’s perineum after it has been torn or cut during childbirth.

From the outset, the narrator of “The Husband Stitch” is interested in the choices she makes and the power to decide: “I have always wanted to choose my moment, and this is the moment I choose” (Machado 4)—selecting a young man at a party to at first have sex with, then date, and ultimately marry. The story, in this way, upends conventional notions of male-female power dynamics, opening with the narrator stating: “In the beginning, I know I want him before he does. This isn’t how things are done, but this is how I am going to do them” (3). “In the beginning” marks not only the beginning of the story, but the creation of the world, putting god-like power in the narrator’s hands. Her boyfriend-husband is incensed with her refusal to disclose the reason for her ribbon; unable to accept that a woman has information she makes inaccessible to him. Her husband’s curiosity and anger at her ribbon is mirrored in their son, who at first playfully touches her throat and then more hungrily demands for its discovery. Both man and boy are demanding of access to all forms of knowledge and enraged at the narrator’s prohibition to her secret. It is important to note that her secret is intimately linked to her body, its unity, and stability, which ultimately are undone.

In their old age, just as in the original fairy tale, the narrator resigns herself to her husband’s desires: “‘Then,’ I say, ‘do what you want’” (30). Untying her ribbon, the narrator’s “lopped head tips backward” and rolls off the bed, making her “feel as lonely as [she has] ever been” (31). The decision to unmake herself, literally unstitching her own head to appease her husband, is intimately linked to her affective position—she is separated not only from herself but husband, son, and community. We should ask ourselves were agency lies within the story and if the narrator’s permission is a consensual one or done from her own volition. I would like to propose that while the narrator is pushed by the male insistence and demands of her husband, it is crucial that the ribbon is only untied after she verbally allows him to do so; realizing there will never be a space or time in which she will not be demanded upon to account for her knowledge, the narrator chooses to undo herself.

Much as the ribbon causes confusion and anger because of the unanswerable questions it raises. Women’s bodies themselves become sources of mystery and fear in “Real Women Have Bodies.” Working at a dress shop, Glam, the story’s narrator discovers that she has been selling dresses inhabited by disembodied women, sewn into the material where they occupy the space in dress form: “She presses herself into it, and there is no resistance, only a sense of an ice cube melting in the summer air. The needle—trailed by thread of guileless gold—winks as Petra’s mother plunges it through the girl’s skin. The fabric takes the needle too” (134). The imagery of the needle and thread combines, as with “The Husband Stitch,” suggestions of bondage and domesticity, themselves associated with notions of sexuality and womanhood (of course, bondage can refer to a woman’s containment within social norms but also the sexual practice of bondage).

Yet it is the mystery of the women’s disappearance that lends the female body so much power in the narrative. Slowly fading away, the cause for the disappearance of hundreds of women is never explained, leading people to imbue them with unearthly power and danger: “It turns out that they think that the faded women are doing this sort of—I don’t know, I guess you’d call it terrorism? They’re getting themselves into electrical systems and fucking up servers and ATMs and voting machines. Protesting,” Petra explains to the narrator (144). Yet the fear that they instill come not from overtly aggressive or violent acts, but through silence and passivity, the unmaking of themselves as corporeal beings. The narrator describes the women in the dress-making room as “glowing faintly, like afterthoughts” (134) and their expression as indecipherable: “The faded woman won’t look away. She smiles. Or maybe she is grimacing” (145). She importantly also understands that all women are destined to disappear: “Soon, I’ll be nothing more, too. None of us will make it to the end” (147). The narrator implicates not only herself but all women in this disappearance, positioning the world as an inhabitable space for them as-is. However, as she has seen, women take on a new form of passive resistance which they refuse to escape.

I’d like to conclude by thinking of the story “Eight Bites,” in which a woman undergoes gastric band surgery in order to lose weight. Her sisters have undergone this surgery—implicating fatness as well as the desire for thinness and surgery as part of family tradition (kinship formations?). Unlike her sisters, however, the protagonist’s surgery does not have the same desired effects. In fact, the surgery not only causes a rift between her and her daughter, but unlike the “ghosts” that haunt her sister’s, the supernatural entity that haunts her house after the surgery is one that causes a form of externalized deep anger toward the self.

Not only does “Eight Bites” touch upon the toxic message women have internalized about body image, but also about the pleasures of self-harm and abnegation. The narrator’s self-inflicted violence finds its most poignant expression through the supernatural being that haunts her post-surgery: her fat-ghost; the fat she has attempted to get rid of but that now resides in her house. Before the surgery, the narrator desires the possibility to “relinquish control[,]” making everything “right again” (158); a desire to be unthinking and perhaps uncritical of her own body, much like the oyster she eats before surgery: “I was jealous of the oysters. They never had to think about themselves” (157). Much like Yeong-hye, the narrator of “Eight Bites” wishes for an undoing of the self, a state of mollusk-like (plant-like) mindlessness.

However, the fat-ghost disallows this and acts as a continual reminder of her decision inspired by self-hatred. Much like the oyster, her fat-ghost “is a body with nothing it needs” (165) and inspires deep, instinctual anger in the narrator: “I do not know that I am kicking her until I am kicking her. She has nothing and I feel nothing except she seems to solidify before my foot meets her, and so every kick is more satisfying than the last” (165). The act of kicking not only makes the ghost robust and entity-like, but also provides pleasure for our narrator. Here, she is exerting violence on an externalized formation of the self that she has originally rejected through the surgery but that has remained as a haunting presence. In fact, the story provides no possibility for comfort: realizing she was wrong in her decision, the narrator imagines the time of her death when she will ask forgiveness of the fat-ghost. Importantly, the haunting acts as an eternal manifestation of self-hatred created by the narrator herself: “She will outlive me by a hundred million years; more, even. She will outlive my daughter, and my daughter’s daughter, and the earth will teem with her and her kind, their inscrutable forms and unknowable destinies” (167). As with all the women of Her Body and Other Parties, female presence here enacts a form of mystery that can never be answered.

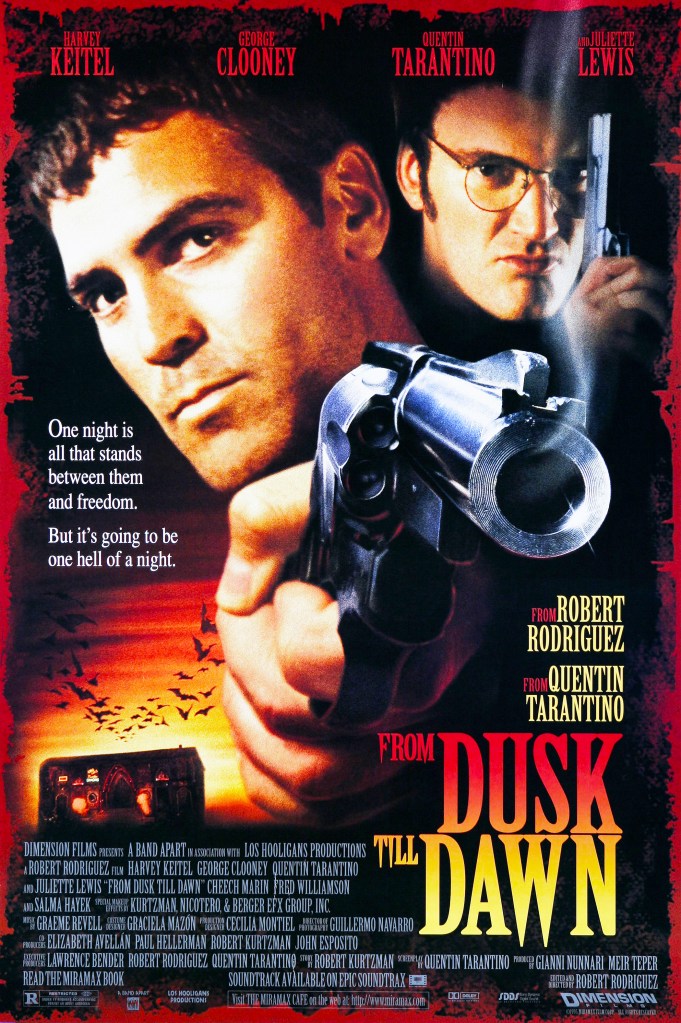

Excessive Aesthetics in Robert Rodriguez’s From Dusk Till Dawn

Robert Rodriguez never disappoints! This semester has been difficult for many reasons, and it seems that students are having a really difficult time. After eight weeks of reading difficult material, and sometimes long novels, this movie seemed to come at the perfect time. Outside of landing right before Halloween weekend, From Dusk Till Dawn generated one our liveliest discussions so far.

This film comes after our conversation of What You See in the Dark, which is a reexamination of Hitchcock’s Psycho, and continues our exploration of border horrors. Next week, we will discuss Fernando Flores’s Tears of the Trufflepig, and I’m so curious to see if students connect with this weird novel.

It’s not surprising that only one student in the class had seen From Dusk Till Dawn, and it was particularly interesting putting not only the B-list and cult classic actors in context for them, but also contextualizing the importance of the mid-1990s for this geopolitical space, especially as it relates to NAFTA and the war on drugs. The film has various turns or shifts in tone that I find particularly interesting. The film opens with what seems to be a Western/thriller/crime-drama intent (a Quentin Tarantino tone, I would call it) in the convenience, as Seth and Richie Gecko attempt to hide as they escape after their bank robbery. Yet, what seems to be the promise of this opening completely shifts. Meeting the Fuller family in a Texas motel, the Gecko brothers take them and their RV hostage and enter Mexico, stopping at the Titty Twister. Their entrance in Mexico is full of lights, fire, uproar, and presents this new landscape as one hedonism and danger. The third turn takes place when the dancers of the Twister transform into vampires, extending the over-the-topness we see as the motorhome approaches the bar even further; taking the excessiveness of camp aesthetics and turning it “up to eleven.” I asked my students to consider how the motorhome could be consider a reconstituted haunted house, equipped with its own monster (Richie: depraved sociopath) as it approaches another haunted space and monster (the bar and its vampires).

Our class on From Dusk Till Dawn spent a great deal of time discussing how the film defines criminality and monstrousness in strange and unconventional ways, staging a “good” criminal (Seth Gecko) who must rid himself of the “bad” criminal (Richie Gecko). In fact, the argument many made was that as a more ethical representation of “badness,” Seth is allowed to survive in conjunction with the virginal Kate (Juliette Lewis). Richie’s childlike voice and demeanor hides something more sinister underneath: an instinctual sadism and desire for violence and blood akin to the vampire itself. The movie, my students argued, therefore must rid itself of Richie, much like it must destroy the vampire.

Interestingly, Richie’s murder of the bank teller (before entering Mexico) is only shown in brief cuts that move back and forth between the victim’s body and Seth’s face as he encounters it. The violence performed on her body is never shown and neither is the aftermath of this violence (we only see her body in the distance and blurred at that). This is in stark opposition to the violence performed on the Mexican woman’s body (woman-cum-vampire). In fact, Cheech Marin’s (Chet Pussy) speech as the motorhome approaches the Titty Twister promises gendered violence that is paradoxically always linked with pleasure and excessive camp aesthetics:

This “slashing pussy in half” is, indeed, what takes place through the remainder of the film. As a class we discussed how Satanico Pandemonio (Selma Hayek) introduces a sexuality that is ancient and powerful, as she dances with a large boa (what more phallic than that?) around her neck. Her threat to Seth is one that promises female domination and control over a male Anglo-American body; one that the film cannot endorse:

“I’m not gonna drain you completely. You’re gonna turn for me. You’ll be my slave. You’ll live for me. You’ll eat bugs because I order it. Why? Because I don’t think you’re worthy of human blood. You’ll feed on the blood of stray dogs. You’ll be my foot stool. And at my command, you’ll lick the dog shit from my boot heel. Since you’ll be my dog, your new name will be ‘Spot.’ Welcome to slavery.”

Looming over him, the achievement of Satanico Pandemonio’s threat is impossible to imagine, both because she is vampire and woman. As many of my students pointed out––particularly my female students––From Dusk Till Dawn is highly problematic and seems terribly outdated. As we can see from the scene above, the only spaces women can inhabit is that of exposed breasts or slashed pussies (following the film’s own terminology). The only “woman” (if we can call her that) it can imagine surviving is Kate, the cross-bearing virginal daughter. Following horror film conventions, she is the final girl who emerges covered in the blood of monsters (alongside that of her family).

For all of its fabulous campiness and in spite of its outmoded gender politics (it seems that Tarantino still needs to get up-to-date somewhat), I find the final scene particularly promising. As Seth and then Kate drive away from the Titty Twister, the camera pans upward into an areal shot of the landscape, revealing an ancient temple underneath the bar with what seems to be hundreds of eighteen-wheelers: a truck cemetery.

Perhaps the temple signals a longer history of resistance on the U.S.-Mexico border, that while depicted through problematic representations of female sexuality (which apparently must be destroyed), also formulates an anti-capitalist blockade that will continue. Admittedly my students were not fully committed to this reading, arguing that I was giving the movie too much credit and asking how such a brief inclusion could carry so much weight for the film. As always, students continue to push my thinking and teaching, and I’m thrilled to see what they say about our next text.

Seeing and Being Seen: Teaching Manuel Muñoz’s What You See in the Dark

Manuel Muñoz’s novel, What You See in the Dark (2011), is a reimagination of Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960). I love this novel, even if it’s not always a favorite of my students. But I was so pleasantly surprised by my students reactions to this semester; a lot of them said it’s their favorite book so far. Perhaps it’s a testament to Muñoz’s gorgeous prose and the way that he cinematically presents the world of Bakersfield.

There are also a few things I’ve noted this semester I hadn’t before. The first thing is that students of this generation take media for granted. This is not a value judgement, but it’s fascinating to see how media technologies are so ingrained into our daily lives that we expect fame, celebrity, and film and TV to be at our fingertips at all times. We spent a big portion of our initial two class on the novel talking about Hitchcock and the revolutionary effect Psycho had not only on filmmaking but on notions of fame. You can see good examples of how this happened, here and here. The second thing I noticed, and which made my so happy, is that students are reading in new and more careful ways. In fact, one of my students, in commenting about the novel, said that since being a part of this class, she’s noticing new things and reading differently. It makes me feel so proud that I’m helping develop their close reading skills!

As we always do when we start a text, we spent a large portion of the first class laying a foundation for our discussion: parsing out major themes, characters, plot points, time markers, and points of view. After laying this foundation, we spent some time thinking about POV and the significance that the first chapter, which is narrated by Candy, is in the second person. Students noticed the immediacy this POV lends the narrative and the way it implicates the reader in the what some students called “creepy” and “stalkery” actions. In fact, students noted how from the opening page, What You See in the Dark not only centralizes seeing and being seen, but makes cinematic narration an essential element of the text

You can see my annotated copy of the novel’s first page and the way that looking and eyes are everywhere. The centrality of eyes and looking in conjunction with the shifting points of view, my students noted, demonstrates how the novel is foregrounding the impossibility of knowing anything for certain (the “Truth”). Moving between Candy, Teresa, the Actress, and Arlene, the novel shows the importance of perception and how our prejudices affect our daily lives and those of others.

Importantly, we don’t find out Teresa’s identity until page 25 of the novel, after she’s been killed. In many ways, like Janet Leigh’s character in Pscyho, Teresa haunts the novel from the outset. Moreover, she is already dead by the time we meet her in the novel, a ghost.

On Thursday, we continued our conversation about the role of perception, seeing, and notions of “truth.” The novel does an amazing job drawing a connection between the lives of the women in the novel and the film, and my students and I discussed how the Actress is so desirous to give her character interiority, while the Director simply treats her as a prop for the film. In many ways, Teresa is also a prop for readers, or perhaps Muñoz is attempting to remedy the misogynistic treatment of women Hitchcock is notorious for. Chapter by chapter, readers learn about each woman’s desires, struggles, regrets, and even though there is no way of getting at the “truth,” we can see many sides of it.

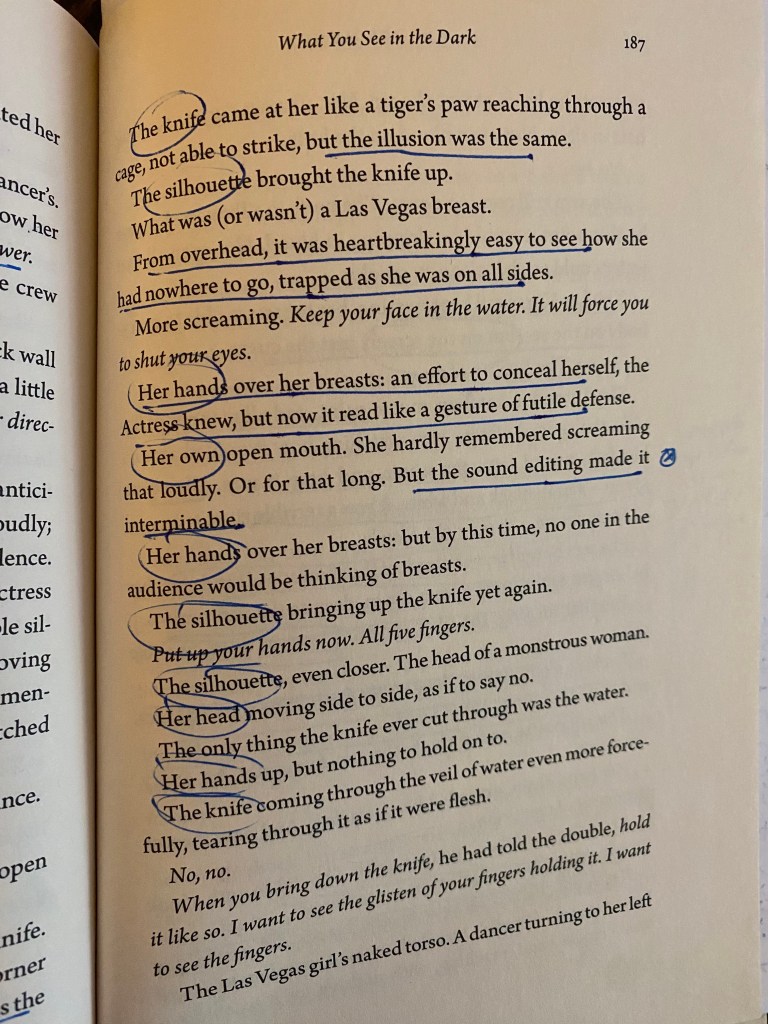

Lastly, I’ll note that our class ended with an in-depth discussion about Pscyho‘s shower scene (storyboarded below) and how it compares to Teresa’s death in the novel.

As you can see from both the storyboard and my annotated page from the novel, the shower scene is meticulously described. So much attention is spent on the killing of the Actress, artistically rendered and, in fact, the text mirrors the content in form by breaking her body apart like the knife does. My students also noted how, unlike the Actress’s killings on screen, Teresa’s murder happens off camera, giving it much more portentous weight, while also shrouding it in mystery.

I’m so excited to see what students think about the ending of What You See in the Dark!

Exile, Disaster, and Science Fiction in Michael Zapata’s The Lost Book of Adana Moreau

Last week my students and I started our discussion of The Lost Book of Adana Moreau (2020). This is the second time I’m reading the book and teaching it as well. I *love* reading books alongside my students, especially because of the discoveries that happen as we talk about the text––we’re both seeing things for the first time. I also love having disagreements in the classroom when it comes to the books I’m teaching. I find The Lost Book really moving but for some reason I was having a hard time getting my students talking about. I think the novel deals with really complex issues and, most importantly, doesn’t provide easy answers, and perhaps this is why students were shy about discussing the novel. In fact, the way in was simply asking them, “Do you like the book?” What ensued was a great debate not only about whether they were liking Zapata’s text, but also about our own readerly practices, expectations from a plot, and how we annotate a text in order to examine it in depth.

One of my favorite elements about The Lost Book is the way it exceeds expectations––the plot will not easily conclude, science fiction is central to the plot, yet the novel is not technically genre fiction, the labyrinthian stories within the novel will be spelled out for us. Much like our first book this semester, Oscar Wao, Zapata’s is deeply concerned with the tropes of genre fiction for the story it is trying to tell, and in its speculative orientations also reveals the otherworldly nature of Latinx histories and identity formations. Most importantly, it paints a vast global network centered around the otherworldly that helps us think about the formations of race, ethnicity, and national belonging while also surpassing entrenched notions of latinidad. Beginning in the Dominican Republic, Zapata’s novel, like Oscar Wao, also presents the Caribbean as science fictional, while not explicitly naming it as cursed. Zapata is Ecuadorian American but focuses on archipelagic spaces and oceanic contact zones, building an unexpected network between the Dominican Republic, New Orleans, Chicago, Chile, and Israel in a moving story about neo/coloniality, diaspora, the impossible gaps of the historical archive, and storytelling. The Lost Book is framed through the retelling of a lost and then rediscovered science fiction novel, beginning with the 1916 American occupation of the Dominican Republic and ending with Hurricane Katrina in 2005.

An ode to the power of literature (without the elitist demarcations of “high art” versus the “low brow”), The Lost Book underscores the importance of storytelling as well as its complications, touching on notions of narrative artistry, literary marketability, but also about familial connection, the impossibility of encapsulating stories in their entirety, and the passing on of national, ancestral, and individual testimonies. Saul Drower, an Israeli-born Jew receives a package in Chicago that his recently deceased grandfather had been trying to get to a physicist in Chile named Maxwell Moreau. The package contains an unpublished manuscript written almost a hundred years earlier by Maxwell’s mother, Adana, an orphaned Dominican woman who emigrates to New Orleans after the American occupation of the island. The “lost book,” A Model Earth, is the sequel to a novel published in 1929, Lost City, and continues its investigation of multiple universes. Zapata, more importantly, implements the tropes of speculative fiction to illuminate a Borgesian, labyrinthian tale of immigration, exile, diaspora, coloniality, and repeating patterns of global violence. The novel culminates apocalyptically with Hurricane Katrina, a plot device that greatly emulates Adana’s own writing. “Where does one universe end and another begin?” asks the protagonist of her novels, a Dominican woman who significantly resembles Adana herself. Through this question, Zapata’s novel inspires a multitude of additional ones related to porosity of borders between nation states, generational trauma, networks of literary and familial narratives, and lasting legacies of violence, colonial, imperial, fascistic. Considering Adana’s first science fiction novel, Lost City, Saul cannot fully describe the meaning of the text, yet senses “something in its lingering, peculiar beauty, in the Dominicana’s terrible grace, in the madness of cataclysm, in the pale, feverish eyes of the zombies, in the eternal grief of Santo Domingo, in the dazzling blues of the seas of the Antilles, in the lost paradise of Cartagena, the sweet fragrance of fruit and wild rice […] he had sensed something in its parts but also something beyond its whole” (73). Much like Díaz’s meditation on what disasters reveal and Oscar Wao’s implementation of genre fiction to underscore the cyclical nature of Caribbean haunting, Saul concludes that “every word, every sentence, every passage, every chapter, concluding in the whole vast thing, spoke of exile” (73). Adana’s novel is a metafictional representation of Zapata’s which encapsulates it: the lost book of novel’s title not only exhibits the central role speculative fiction plays for thinking about global networks of catastrophe, violence, diaspora, and exile, but through the lost book itself, centralizes a Latinx speculative fiction archive that could have been. Adana’s lost book—reproduced in the novel by Saul’s grandfather—is an example of what Saidiya Hartman terms “critical fabulation.” As a “model for practice,” critical fabulation is the labor of writing against the limits of the archive while simultaneously perming the “impossibility of representing the lives of the captives precisely through the process of narration” (“Venus in Two Acts”). Scholars working in Latinx speculative fiction then consistently engage in this type of work, and as my own has attempted to show, Latinx literature implements the tools of speculative fiction in unexpected ways. I’m really excited to see how students react to the end of this novel…I’m re-reading along with them and I’m struck with how melancholy this book is. In many ways, The Lost Book seems to tackle the impossibility Hartman writes about: the lost people, stories, and forms of knowledge that are erased because of many (and often intersecting) forms of violence.

It’s Spooky Season!

It’s officially spooky season. Every October I look forward to centering my TV and film watching around all things horror, although I honestly watch horror year-round. This year, I’ve been watching the new Netflix series about Jeffrey Dahmer, which is the platform’s most popular shows, but understandably also come under a lot of criticism. I have also started watching the docuseries about Armie Hammer and the sexual abuse and cannibalism allegations against him.

There have been a lot of exciting new horror film releases in the past few years; so many that it’s hard to keep up! I’ve made a watch list for myself for those films I’m the most excited about watching this Halloween season. Some of these I’ve watched already (marked with an asterisk), others I can’t wait to see!

*The Innocents –– 96% on Rotten Tomatoes –– I was really resistant about watching this film, but am so glad I did. Centering the experiences of four children, this film is deeply interested in fantasy, ethics, and the formation of kinship.

Halloween Ends–– last year during Halloween season, I watched all movies in the Halloween series, following all three different timelines. So, of course, I’m thrilled to see how this new addition fits within the Halloween and Michael Myers lore.

Smile

*Fresh

Earwig

Watcher

*MEN

The Invitation

Bodies Bodies Bodies

Prey

Hatching

*Crimes of the Future

The Cellar

*Resurrection

Hypochondriac

*Lamb

*Black Phone

*In the Earth

*Titane

*1What Josiah Saw

*Saint Maude

*You Won’t Be Alone

She Will

Little Joe

Teaching Junot Díaz’s _The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao_ in 2022

I have been writing about and teaching The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao (2007) for almost a decade now, and what I am most impressed with is how the experience and reception of the book has changed over the years. When I taught this book in graduate school, I meditated on how difficult it is to teach books one loves or knows too well. I think I still feel this way while I can the novel’s limitations. After having taught this book so many times, I still have difficulties creating a narrative arc for my lessons, and I worry that my students don’t come away with a coherent grasp of the novel. I also think that Oscar Wao in particular is difficult to teach, and sometimes consider that to teach this book I would need an entire semester! I have to admit that I used to love The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Was (2007). I found myself seduced by the writing, the narration, the scope and ambition of its project. While I wouldn’t say I love the book anymore, I am still deeply invested in it. One of the chapters in my book is dedicated to Oscar Wao (alongside other works by Díaz). Yet, it’s difficult to contend with the novel, and Díaz himself, in light of the various sexual assault and misconduct allegations against him in April and May 2018.

Although I don’t feel the same as I once did about Oscar Wao, I find it to be an important work not only of Latinx fiction, but one that centralizes the speculative and monstrosity––a crucial element for our course this semester, and my work generally. I’m also someone who continues to think about this novel and Díaz’s position within the Latinx and American literary canon. So, I was nervous about teaching this text in “Monsters, Horrors, and Hauntings in Latinx Literature.” Partly, it is a complicated text that needs a great deal of parsing, but also I was concerned with the statement teaching this novel would have: what does it mean asking students to buy this novel in light of the #MeToo allegations against Díaz? Why not ask students to read another Dominican American text instead (another Afro-Latinx novel etc. instead)? However, I came to the conclusion that for the purposes of this course, which centralize monstrosity, haunting, and violence, Oscar Wao represents these themes and ideas in important ways. I also wanted to reframe the conversation of this novel to centralize depictions of gender and sexual violence––issues that most scholars have discussed as central issues the novel writes against.

As with previous texts this semester, students in this course continue to impress me with their dedication to the work. They have really raised my expectations for future classes and groups of students. Students came to the text with insight and meaningful questions that pushed our discussions in important ways. I’ve been thinking about this article from Remezcla about how Díaz’s work has transformed the literary marketplace and the Latinx literary scene in particular. In many ways, Díaz’s work since Drown has put other Latinx writers on the literary map and helped English-speaking readers reimagine Latin American, the Caribbean, and the type of fiction that emanates from these spaces (i.e.: reconfigured Latinx literature as being more than Magical Realism).

There has been a great deal of scholarship on Díaz’s work since the publication of Drown, but most scholarly attention has certainly focused on Oscar Wao. As I’ve said in conference papers and in my book, Díaz is a central figure in Latinx literature (probably the one Latinx author non-specialists would recognize), much as Sandra Cisneros, Cristina García, or Oscar Hijuelos were before him. However, unlike the Latinx writers of the 1980s and 1990s, Díaz has assumed celebrity status, drawing crowds to his readings, appearing in podscasts (On Being, New York Public Library, This American Life, and NPR’s Alt Latino, to name a few) and dominating the pages of The New Yorker (seventeen authored pieces since 1996), one of the literary trend-setters of the U.S. Most recently, Duke University Press published Junot Díaz and the Decolonial Imagination (2016), an edited collection particularly useful for the Díaz scholar, and which originated from a conference centered on his work. Besides containing scholarship by important Latinx academics, this collection also has an interview with Díaz that is important for thinking about the novel and Yunior as a narrator––”The Search for Decolonial Love: A Conversation between Junot Díaz and Paula M. L. Moya.” In it, Díaz states:

“In Oscar Wao we have a family that has fled, half-destroyed, from one of the rape incubators of the New World, and they are trying to find love. But not just any love. How can there be “just any love” given the history of rape and sexual violence that created the Caribbean — that Trujillo uses in the novel? The kind of love that I was interested in, that my characters long for intuitively, is the only kind of love that could liberate them from that horrible legacy of colonial violence. I am speaking about decolonial love.”

Indeed, much of the conversation about The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao in our class focused on its representations of the Caribbean, the haunting of the past and personal trauma (fukú), and the possibility of overcoming this history, or what Yunior calls a “zafa”: a counter-spell that could foment a regenerative future for him and the Dominican people and its diaspora. As one of my students pointed out in our two-week discussion, the de León family saga (and through his narration, Yunior’s personal history) acts as a case study for discussions of Dominican and Caribbean experiences of trauma.

Of nineteen students, only two had previously read the novel (one in my course last semester), perhaps a symptom of the status Latinx literature holds within larger conversations of “American” literary and cultural studies and the “American” literary canon––even as Díaz is important within these fields. It was wonderful seeing students’ reactions to reading this novel for the first time, and I was particularly impressed with their tackling of Spanish words, phrases, and slang, and their in-depth appreciation of the extensive footnotes that run throughout the text.

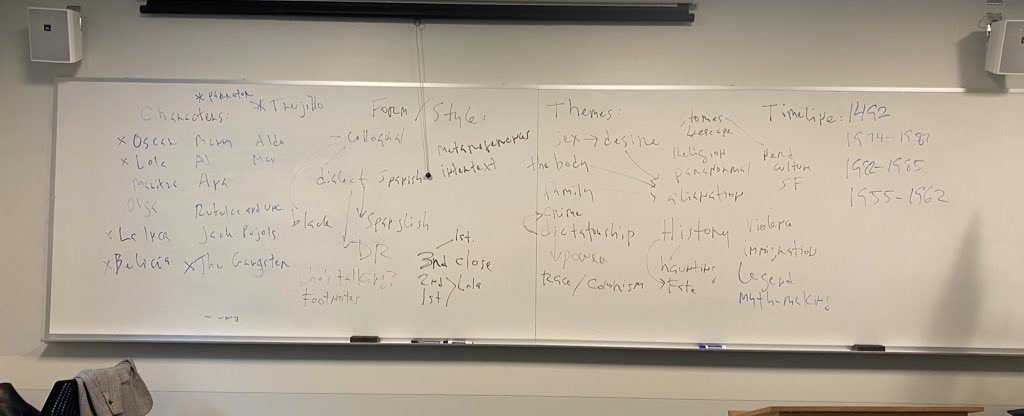

As with most texts, we began our discussion of Oscar Wao visually laying-out the major themes and concerns in the text:

Our introductory class period was mostly spent close reading the epigraphs of the novel, the first from Marvel’s Fantastic Four:

Of what import are brief, nameless lives…to Galactus?”

Fantastic Four

Stan Lee and Jack Kirby

(Vol. I, No. 49, April 1966)

The second is an excerpt from Derek Walcott’s poem, “Schooner Flight”:

Christ have mercy on all sleeping things!

From that dog rotting down Wrightson Road

to when I was a dog on these streets;

if loving these island must be my load,

out of corruption my soul takes wings,

But they had started to poison my soul

with their big house, big car, big-time bohbohl,

coolie, nigger, Syrian, and French Creole,

so I leave it for them and their carnival—

I taking a sea-bath, I gone down the road.

I have known these islands from Monos to Nassau,

a rusty head sailor with sea-green eyes

that they nickname Shabine, the patois for

any red nigger, and I, Shabine, saw

when these slums of empire was paradise.

I’m just a red nigger who love the sea,

I had a sound colonial education,

I have Dutch, nigger, and English in me,

and either I’m nobody, or I’m a nation.

This led us to a discussion of Galactus, his role in the comic book, and how these epigraph might be related to the novel’s title. A cosmic entity who consumes planets in order to sustain life force, Galactus elicits notions of immense force and power. Yet students smartly observed how the novel’s title introduces Oscar as “brief” yet “wondrous,” a word that connotes extra-ordinaryness and otherworldly-ness that perhaps could combat Galactus’ presence. The epigraph from The Fantastic Four also introduces readers to ongoing conversations surrounding the study of popular culture and its relation to notions of “high art.” I pointed students to the careful attention to detail the text lends to this reference, citing not only the comic book’s authors, but also volume number, issue number, and precise date of release (month, day, and year). I asked students to consider this archival minutia––geekery if I’ve ever seen any––in relation to how Walcott’s poem excerpt is referenced, i.e.: without the same citational details of the previous epigraph. In effect, the discrepancies here point readers to understand science fiction, popular culture, and fantasy references to be of more importance in the novel (for more, you can hear Díaz speak about this in the New York Public Library podcast). Although I agree with Díaz that an important secondary or tertiary narrative can be found within these references, the “high” literary details such as the Noble Laureate’s poetry, allusions to Joseph Conrad (“The beauty! The beauty!”), and references to canonical authors are significant for this text and our understanding of Yunior as a burgeoning creative writer. As our discussion of Oscar Wao proceeded, I attempted to place the novel within other literary movements, most importantly postmodern pastiche and the post-9/11 novel.

Notions of uncertainty and cataclysmic terror open the novel, and we spent most of this first class period discussing the importance of fukú americanus as a foundational structure for our reading practices and understanding of the novel’s characters, diasporic history, and potentials for redemption. I asked students to consider the following questions as they continued their reading of the book, keeping fukú as an essential keyword in the plot: How does fukú structure the novel? How does this term introduce us to Antillean history and the potentials for Dominicans in the DR and its diaspora? How does this term teach us to the read everything that follows?

Like the texts we read before this one, our discussion centered on the notion of haunting and the possibility of escaping the horrors of history and trauma-as-lineage. As with We the Animals, our conversation about Oscar Wao addressed the human body, Oscar’s obesity and Belicia’s hypersexual representations. I posited that throughout the novel the female body is presented as a world-destroying presence, a harbinger of (male) apocalypse. For example, the novel describes the Gangster’s desire for Belicia as follows:

I mean, what straing middle-aged brother has not attempted to regenerate himself throughthe alchemy of young pussy. And if what she often said to her daughter was true, Beli had some of the finest pussy around. The sexy isthmus of her waist alone could have launched a thousand yolas, and while the upper-class boys might have had their issues with her, the Gangster was a man of the world, had fucked more prietas than you could count. He didn’t care about that shit. What he wanted was to suck Beli’s enormous breasts, to fuck her pussy until it was mango-juice swamp, to spoil her senseless so that Cuba and his failure there disappeared. (123-124)

In its depiction of Belicia, the novel not only sexually objectifies the Afro-Caribbean female body but also transforms her into the earthy arena on which past historical events such as the Cuban Revolution are explored. The novel considers the hemispheric turbulence caused by Cuban Revolution through its individual effects and its repercussions on the female body, staging sexual intercourse as an extension of dictatorial violence. The Gangster’s future after the Revolution appears “cloudy” (123), and the act of “fuck[ing]” Belicia enables the transformation of her vagina into a stereotypically natural (and tropical) space of danger, stagnation, and death that erases entire political movements. There is much more to say about this passage, but this is just a brief close reading I performed for my students to demonstrate how to “mine the text for meaning” (a phrase I use to talk about analyzing texts).

In effect, there is so much to say about this novel. However, I want to conclude this post about teaching Oscar Wao by commenting on our discussion on the novel’s silences and those things left unsaid (something that returned us again to Morrison’s work). Throughout our conversation we also talked about Yunior’s reliability as a narrator, the novel’s multilinguality and code-switching (i.e.: who is this novel written for?), the sexual politics and misogyny that runs throughout the text, and the footnotes as presenting a counter-narrative to the Oscar and Yunior’s story.

There are many silences in The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao, as can be seen in the various references to “página en blanco” (blank page/s) (78, 90, 119). As with the unknowable words of the mysterious Mongoose that rescues Beli from the cane fields––“_____ _____ _____” (301)—and the words Yunior cannot say to Lola (represented textually identical to the Mongoose’s)—“and I’d finally try to say the words that could have saved us. _____ _____ _____” (327)—the de León family history and the nation’s past is unrecoverable. Abelard, Oscar’s grandfather is rumored to have written a book about the horrors of Trujillo and the cataclysmic past of the Dominican Republic. However, this book, like Oscar’s final letter is never read/found. Throughout our discussion on the novel’s silences, I presented an argument to my students about the possibilities of representing the horrors of Caribbean history and its haunting in the present, and whether the novel can indeed act as a “zafa.” Like Oscar’s excessive physical description and Belicia’s hyper-sexuality, I argued to my students that the novel demonstrates the impossibility of depicting the horrors of history through narrative language. The text reverts to multiple beginnings and endings, excessive descriptions of violence (physical and emotional), multiple references to popular culture and “high art,” and those things left unsaid in order to attempt to depict the haunting of Caribbean violence, without completely being able to do so.

Like Yunior, I am finding it difficult to end my writing about this story. I leave you with this reading by Díaz from the novel. He is a wonderful public speaker and reader of his own work, and I showed my students this clip to demonstrate the power of his narrative voice:

There is so much scholarship on Díaz and Oscar Wao. The following are so of my favorite articles and chapters about this work:

Hanna, Monica. “‘Reassembling the Fragments’: Battling Historiographies, Caribbean Discourse, and Nerd Genres in Junot Díaz’s The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao.” Callaloo32, no. 2 (2010): 498–520.

Machado Sáez, Elena. “Dictating Diaspora: Gendering Postcolonial Violence in Junot Díaz and Edwidge Danticat.” Market Aesthetics: The Purchase of the Past in Caribbean Diasporic Fiction, University of Virginia Press, 2015, pp. 154–96.

Miller, T.S. “Preternatural Narration and the Lens of Genre Fiction in Junot Díaz’s The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao.” Science Fiction Studies 38, no. 1 (2011): 92–114.

Saldívar, José David. “Conjectures on ‘Americanity’ and Junot Díaz’s ‘Fuku Americanus’ in The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao.” The Global South 5, no. 1 (Spring 2011): 120–36.

Vargas, Jennifer Harford. “Dictating a Zafa: The Power of Narrative Form in Junot Díaz’s The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao.” MELUS: Multi-Ethnic Literature of the U.S. 39, no. 3 (2014): 8–30.

Further Díaz reading:

“Watching Spider-Man in Santo Domingo,” The New Yorker, November 20, 2017.

“Under President Trump, Radical Hope is Our Best Weapon,” The New Yorker, November 21, 2016

“MFA vs. POC,” The New Yorker, April 30, 2014

“Loving Ray Bradbury,” The New Yorker, June 6, 2012

Polish “Vampire” Grave: Thinking about Halberstam’s Skin Shows

Once you start thinking about monsters, start talking about them, they are everywhere. Of course, a day after the start of the semester, The Washington Post published a fascinating story about the remains of a Polish woman who was buried with a sickle around her neck and padlock around her big toe––tools that would incapacitate and kill her should she come back to un-life. As my students and I meditate on the meanings of monsters––why we create them, what types of anxieties they mirror in a particular time and place––I return to the importance of J. Jack Halberstam’s introduction to Skin Shows (1995).

Halberstam begins his exploration about the Gothic monster with Buffalo Bill, the serial murderer of The Silence of Lambs, who is killing women for their skin, making himself a “woman suit.” Halberstam uses the occasion of Bill’s patchwork to think about Gothic monsters and nineteenth century literature. The monster here is a “sutured beast of gender, sex, and sexuality” (1), and like Cohen’s definition, in which the creation of the monster is an amalgam of various anxieties, Halberstam centralizes not only gender and sexuality but also how they are enacted on the body.

The “meaning making machines” of Halberstam’s definition of the monster, like Cohen’s, threaten boundaries by showing us what is beyond these demarcations, and exhibit ornamental excess that create fear precisely because of these extreme forms. The Polish “vampire” reminds us of Skin Shows important argument about how the monster reveals the fears that surround particular types of bodies; those “deviant bodies” that should be, in some cases, expunged.

Most importantly, Halberstam’s definition shows how monsters produce race, class, gender, subsuming things like class, race, nation into their bodies. Throughout this semester we will read about these “deviant bodies” and about the histories that create them, histories as horrific as the things they create.

Jeffrey Cohen’s “Monster Culture (Seven Theses)”

Unfortunately, I was unable to blog immediately after our class on Thursday. In this class, we focused on Jeffrey Cohen’s “Monster Culture (Seven Theses),” which we will use as a theoretical framework for the entire course. I was thrilled to see students not only enjoyed the essay, but actively engaged with its major tenets. Throughout our discussion, I reminded students of the major questions the essay was addressing: What does the monster do? What function does the monster serve? What effect does it create? and Why have we created monsters?

We also addressed the etymology of the word “monster” and its reverberating effect on our daily use of language: “Monster,” as Cohen explains is a “warning,” as can be seen in words like “demonstrate.” Students were asked to keep these questions and the origin of the word in mind as they read through the semester: If the monster is a warning, if the monster is pointing-out something to us, what is he pointing to, what is he warning us of?

In our discussion of Cohen’s essay, I rewrote the main theses for clearer understandings:

- The Monster is a Cultural Mirror: This thesis stipulates that monsters are a reflection of their culture and mirror to contemporary zeitgeists. The monster, therefore, is not just what it is (i.e.: a wolf-man), but it is also what it signifies, what is projects, represents, reflects. For example, Godzilla is more than the reptilian monster that terrorizes Tokyo, but also a reflection of the Japanese post-nuclear experience and fear of physical transformations (deformations, mutations) because of nuclear fallout.

2. The Monster is a Temporal Mirror: This thesis is the most enticing to me, and the one students found the most intriguing and the one we focused on the most. Asserting that monster are elusive and shifty creatures, this thesis upholds that our creations are difficult to pin down and, therefore, must be examined within specific time periods. That is, the monster is always a reflection of its time; it always escapes the a static final embodiment. In other words, vampires (an example Cohen uses) are not static beings that always signify the same thing, but project different anxieties that reflect, for example, a culture’s shifting view of sexuality. Bram Stoker’s original nineteenth-century novel, Dracula, could be read as an indirect way to address deviant forms of sexuality. I showed students various images of vampires throughout popular culture in order to reflect this point:

The 1922 silent film represents vampires as a way of seeing homosexuality as plague-like: a form of self-loathing in the face of fascism.

Anne Rice’s vampires such as in Interview with the Vampire could be read as a celebration of different modes of sexuality.

Francis Ford Coppola’s film adaptation of Dracula can be read as a medium for discussing (through subtext and indirection) the AIDS epidemic of the late 1980s and early 1990s.

A similar phenomenon can be seen by tracing different manifestation of Batman through the decades. For example, take the Batman from the 1966 television show and compare it to the depiction of the same superhero in the 1980s and 2010s. The campy and countercultural Batman of the 1960s (perhaps an escape from the gritty reality of the Vietnam War) is transformed in the 1990s to a reflection of post-Cold War anxieties and a focus on corporate America and its gritty/darker pitfalls. Lastly, Christopher Nolan’s 2012 The Dark Knight Rises reflects a humorless, bleak Batman and a film obsessed with the dangers of terrorism and the destruction of the nation:

3. The Monster as Challenger of Categories: The monster resists any easy categorization by mixing and mingling different categories that challenges the neat distinctions we make as a culture; challenging us to stretch and rethink our rigid understanding of categories (i.e.: the werewolf is an aberrant amalgamation of wolf and man, being both and neither). By refusing easy categorization, the monster demands us to question the labels and frames that we’ve used to make sense of the world. As such, the monster brings crisis to binaries: “the monster’s very existence if a rebuke to boundary and enclosure” (7).

4. The Monster as Justification/Excuse: Because of the freedom the monster presents, its ability to surpass boundaries and call question to fixed definitions, the monster manifest transgressions in cultural, racial, political, and sexual categories. We apply the label “monster” on those who we wish to exclude, those who wish to harm: To “monster” someone is to drape a veil of simplicity (X = evil) on that which we refuse to confront in all its complexity. Cohen touches upon the history of Native American genocide in the U.S. as an excuse for Western expansion, but this point can be extend to other populations as well (Jewish people in Europe, other indigenous populations in the American hemisphere).

5. The Monster as Border Patrol: The monster also serves as a warning against exploration and transgression. The monster “polices the borders of the possible” (13). As such, the monster culturally prevents mobility (intellectual, geographic, sexual) and acts as a border patrol to keep a society intact, stable, static, etc. Therefore, the monster is created as a bogeyman by conservative forces that wish to prevent change–the monster is a vehicle for normalization. For example, what is the moral of Jurassic Park or Frankenstein but “this is what happens when you play god with science!”?

The monster also acts as a lock on specific doors: do not go play in the woods alone because you know what happened to little Red Riding Hood; if you have sex a man wearing a hockey mask will kill you (or any variation of anti-sex morality of 1980s horror films); do not let women own property or they will become witches, etc.

6. The Monster as a Gateway Drug: The monster is, finally, an escapist fantasy. As a form of repulsion and desire/attraction, the monster acts cultural catharsis: a safe way to release some of our pent up rage and dissatisfaction without rocking the boat in any serious way. The monster is a cultural safety valve; our repressions are channeled by culture into the monster (we “purge” ourselves) so we can go back to work on Monday morning as a nice, docile, compliant members of society. The monster can also be a form of “sublimation.” Instead of acting on our dark desires, we we watch a football game, for example, and release our energies vicariously. The monster, therefore, becomes a form of drug, an “opium of the masses” that makes us “feel better” (i.e.: Carnival, Halloween, the monster as happy hour).

Finally, I showed the class a video from the opening episode of AMC’s The Walking Dead, which depicts ex-sherif Rick Grimes killing a child-zombie after awakening in the postapocalypse.

We discussed the following questions: Why do we like zombies? Why has film, literature, and television seen growing interest in the zombie? Do we find the killing of a child (zombie) satisfying, and if so, why? What “release” does the zombie provide? Onto who’s body are we projected when watching this scene?

The Walking Dead clip led to a fascinating discussion about Kristeva’s notion of “abjection” and our recognition and repulsion of figures of the corpse. We spoke about the ways the zombie exposes those things that should be neatly enclosed (viscera, intestines, brains, etc.) and how this produces a senses of fearful recognition and repugnance. Finally, we spoke about how the zombie enables viewers/readers to experience the joy of the forbidden, such as killing a child.