Last week our course transitioned from the Dominican and Dominican American spaces of Junot Díaz’s The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao to the U.S.-Mexico border. Our first text in this area was Robert Rodriguez’s 1996 film, From Dusk Till Dawn (after spring break we will begin our discussion of Cormac McCarthy’s No Country for Old Men. It makes me incredibly sad that our conversation about this incredible—both in terms of style and problematic depictions—will have to be online because of the COVID-19 outbreak but stay tuned for updates about our online discussions).

Only one student in the course had seen the film, and it was particularly interesting putting not only the B-list and cult classic actors in context for them, but also contextualizing the importance of the mid-1990s for this geopolitical space, especially as it relates to NAFTA and the war on drugs.

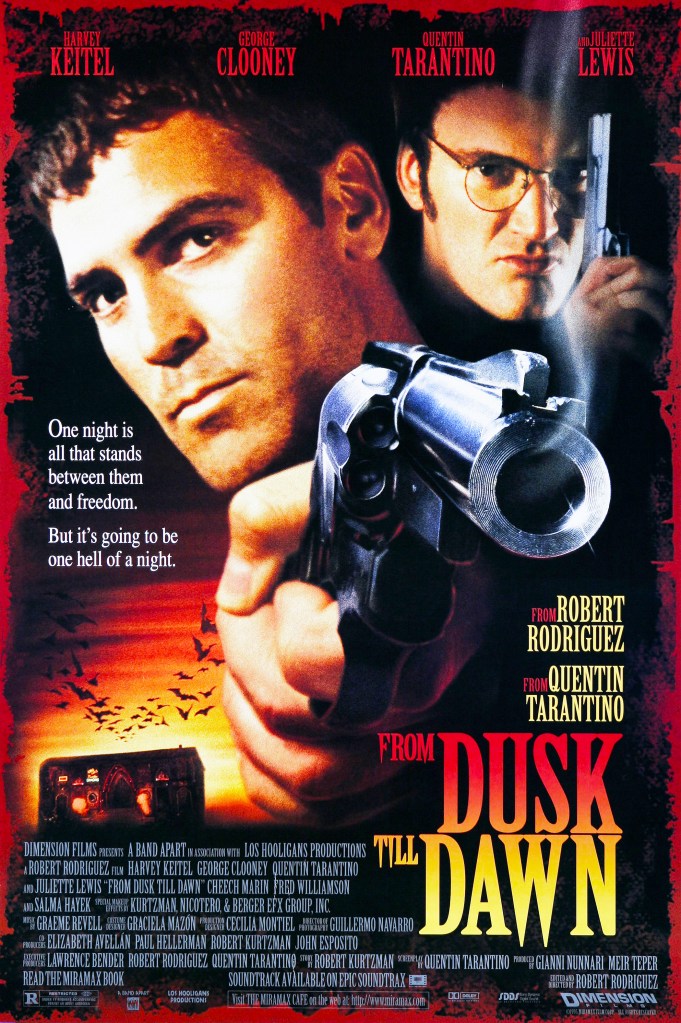

The film has various turns or shifts in tone that I find particularly interesting. The first is the shift from the serious drama (Quentin Tarantino tone, I would call it) convenience store robbery/blow-up to the family (now with the Seth and Richie Gecko in tow, played by George Clooney and Quentin Tarantino, respectively) entering Mexico and approaching the Titty Twister. The third turn takes place when the dancers of the Twister transform into vampires, extending the over-the-topness we see as the motorhome approaches the bar even further; taking the excessiveness of camp aesthetics and turning it “up to eleven.” I asked my students to consider how the motorhome could be consider a reconstituted haunted house, equipped with its own monster (Richie: depraved sociopath) as it approaches another haunted space and monster (the bar and its vampires).

Our class on From Dusk Till Dawn spent a great deal of time discussing how the film defines criminality and monstrousness in strange and unconventional ways, staging a “good” criminal (Seth Gecko) who must rid himself of the “bad” criminal (Richie Gecko). In fact, the argument many made was that as a more ethical representation of “badness,” Seth is allowed to survive in conjunction with the virginal Kate (Juliette Lewis). Richie’s childlike voice and demeanor hides something more sinister underneath: an instinctual sadism and desire for violence and blood akin to the vampire itself. The movie, my students argued, therefore must rid itself of Richie, much like it must destroy the vampire.

Interestingly, Richie’s murder of the bank teller (before entering Mexico) is only shown in brief cuts that move back and forth between the victim’s body and Seth’s face as he encounters it. The violence performed on her body is never shown and neither is the aftermath of this violence (we only see her body in the distance and blurred at that). This is in stark opposition to the violence performed on the Mexican woman’s body (woman-cum-vampire). In fact, Cheech Marin’s (Chet Pussy) speech as the motorhome approaches the Titty Twister promises gendered violence that is paradoxically always linked with pleasure and excessive camp aesthetics:

This “slashing pussy in half” is, indeed, what takes place through the remainder of the film. As a class we discussed how Satanico Pandemonio (Selma Hayek) introduces a sexuality that is ancient and powerful, as she dances with a large boa (what more phallic than that?) around her neck. Her threat to Seth is one that promises female domination and control over a male Anglo-American body; one that the film cannot endorse:

“I’m not gonna drain you completely. You’re gonna turn for me. You’ll be my slave. You’ll live for me. You’ll eat bugs because I order it. Why? Because I don’t think you’re worthy of human blood. You’ll feed on the blood of stray dogs. You’ll be my foot stool. And at my command, you’ll lick the dog shit from my boot heel. Since you’ll be my dog, your new name will be ‘Spot.’ Welcome to slavery.”

Looming over him, the achievement of Satanico Pandemonio’s threat is impossible to imagine, both because she is vampire and woman. As many of my students pointed out––particularly my female students––From Dusk Till Dawn is highly problematic and seems terribly outdated. As we can see from the scene above, the only spaces women can inhabit is that of exposed breasts or slashed pussies (following the film’s own terminology). The only “woman” (if we can call her that) it can imagine surviving is Kate, the cross-bearing virginal daughter. Following horror film conventions, she is the final girl who emerges covered in the blood of monsters (alongside that of her family).

For all of its fabulous campiness and in spite of its outmoded gender politics (it seems that Tarantino still needs to get up-to-date somewhat), I find the final scene particularly promising. As Seth and then Kate drive away from the Titty Twister, the camera pans upward into an areal shot of the landscape, revealing an ancient temple underneath the bar with what seems to be hundreds of eighteen-wheelers: a truck cemetery.

Perhaps the temple signals a longer history of resistance on the U.S.-Mexico border, that while depicted through problematic representations of female sexuality (which apparently must be destroyed), also formulates an anti-capitalist blockade that will continue. Admittedly my students were not fully committed to this reading, arguing that I was giving the movie too much credit and asking how such a brief inclusion could carry so much weight for the film. As always, students in “Monsters, Hauntings, and the Nation” continue to push my thinking and teaching, and I’m going to miss seeing them in-person. Hopefully we can all return to campus soon!