It’s difficult to teach books you love. It’s difficult to teach books you have not only read multiple times but also write about and have (in my opinion) well developed, strong, and original arguments about. I have to admit that I used to love The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Was (2007). I found myself seduced by the writing, the narration, the scope and ambition of its project. While I wouldn’t say I love the book anymore, I am still deeply invested in it. The first chapter of my book project is dedicated to Oscar Wao (alongside other works by Díaz). Yet, it’s difficult to contend with the novel, and Díaz himself, in light of the various sexual assault and misconduct allegations against him in April and May 2018.

Although I don’t feel the same as I once did about Oscar Wao, I find it to be an important work not only of Latinx fiction, but one that centralizes the speculative and monstrosity––a crucial element for our course this semester, and my work generally. I’m also someone who continues to think about this novel and Díaz’s position within the Latinx and American literary canon. So, I was nervous about teaching this text in ”Monsters, Hauntings, and the Nation” this semester. Partly, it is a complicated text that needs a great deal of parsing, but also I was concerned with the statement teaching this novel would have: what does it mean asking students to buy this novel in light of the #MeToo allegations against Díaz? Why not ask students to read another Dominican American text instead (another Afro-Latinx novel etc. instead)? However, I came to the conclusion that for the purposes of this course, which centralize monstrosity, haunting, and violence, Oscar Wao represents these themes and ideas in important ways. I also wanted to reframe the conversation of this novel to centralize depictions of gender and sexual violence––issues that most scholars have discussed as central issues the novel writes against.

As with previous texts this semester, students in this course continue to impress me with their dedication to the work. They have really raised my expectations for future classes and groups of students. Teaching Oscar Wao was a pleasure, as so much in this course has been. As always, students came to the text with insight and meaningful questions that pushed our discussions in important ways. It’s hard to believe, but over a decade has passed since the publication of Oscar Wao. I’ve been thinking about this article from Remezcla about how Díaz’s work has transformed the literary marketplace and the Latinx literary scene in particular. In many ways, Díaz’s work since Drown has put other Latinx writers on the literary map and helped English-speaking readers reimagine Latin American, the Caribbean, and the type of fiction that emanates from these spaces (i.e.: reconfigured Latinx literature as being more than Magical Realism).

There has been a great deal of scholarship on Díaz’s work since the publication of Drown, but most scholarly attention has certainly focused on Oscar Wao. As I’ve said in conference papers and in my book-in-progress, Díaz is our Latinx writer du jour, much as Sandra Cisneros, Cristina García, or Oscar Hijuelos were before him. However, unlike the Latinx writers of the 1980s and 1990s, Díaz has assumed celebrity status, drawing crowds to his readings, appearing in podscasts (On Being, New York Public Library, This American Life, and NPR’s Alt Latino, to name a few) and dominating the pages of The New Yorker (seventeen authored pieces since 1996), one of the literary trend-setters of the U.S. Most recently, Duke University Press published Junot Díaz and the Decolonial Imagination (2016), an edited collection particularly useful for the Díaz scholar, and which originated from a conference centered on his work. Besides containing scholarship by important Latinx academics, this collection also has an interview with Díaz that is important for thinking about the novel and Yunior as a narrator––”The Search for Decolonial Love: A Conversation between Junot Díaz and Paula M. L. Moya.” In it, Díaz states:

“In Oscar Wao we have a family that has fled, half-destroyed, from one of the rape incubators of the New World, and they are trying to find love. But not just any love. How can there be “just any love” given the history of rape and sexual violence that created the Caribbean — that Trujillo uses in the novel? The kind of love that I was interested in, that my characters long for intuitively, is the only kind of love that could liberate them from that horrible legacy of colonial violence. I am speaking about decolonial love.”

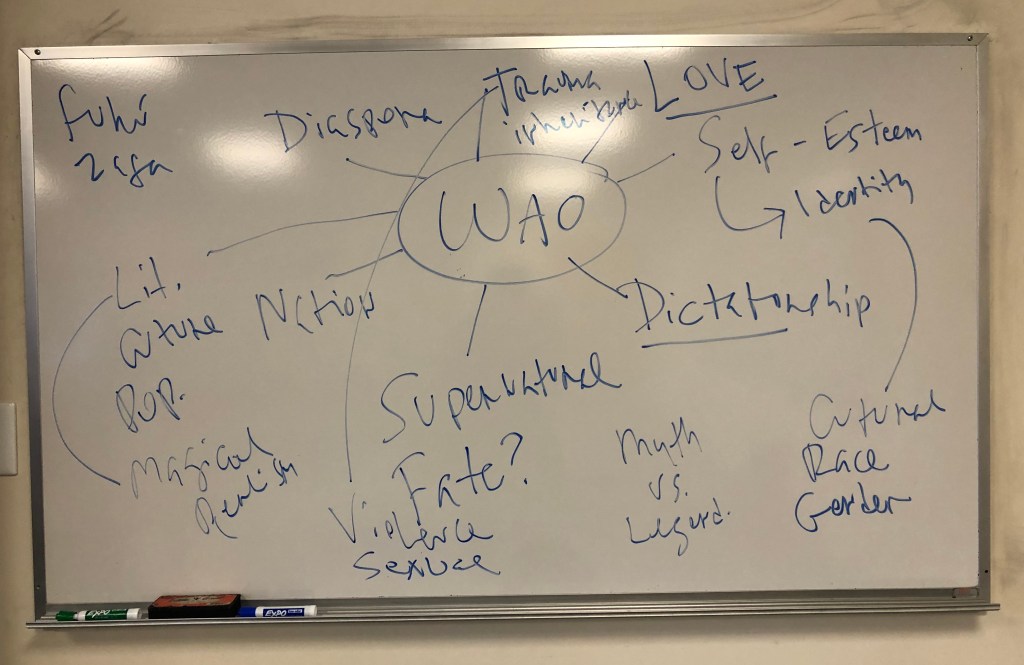

Indeed, much of the conversation about The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao in our class focused on its representations of the Caribbean, the haunting of the past and personal trauma (fukú), and the possibility of overcoming this history, or what Yunior calls a “zafa”: a counter-spell that could foment a regenerative future for him and the Dominican people and its diaspora. As one of my students pointed out in our two-week discussion, the de León family saga (and through his narration, Yunior’s personal history) acts as a case study for discussions of Dominican and Caribbean experiences of trauma.

Of nineteen students, only two had previously read the novel (one in my course last semester), perhaps a symptom of the status Latinx literature holds within larger conversations of “American” literary and cultural studies and the “American” literary canon––even as Díaz is important within these fields. It was wonderful seeing students’ reactions to reading this novel for the first time, and I was particularly impressed with their tackling of Spanish words, phrases, and slang, and their in-depth appreciation of the extensive footnotes that run throughout the text.

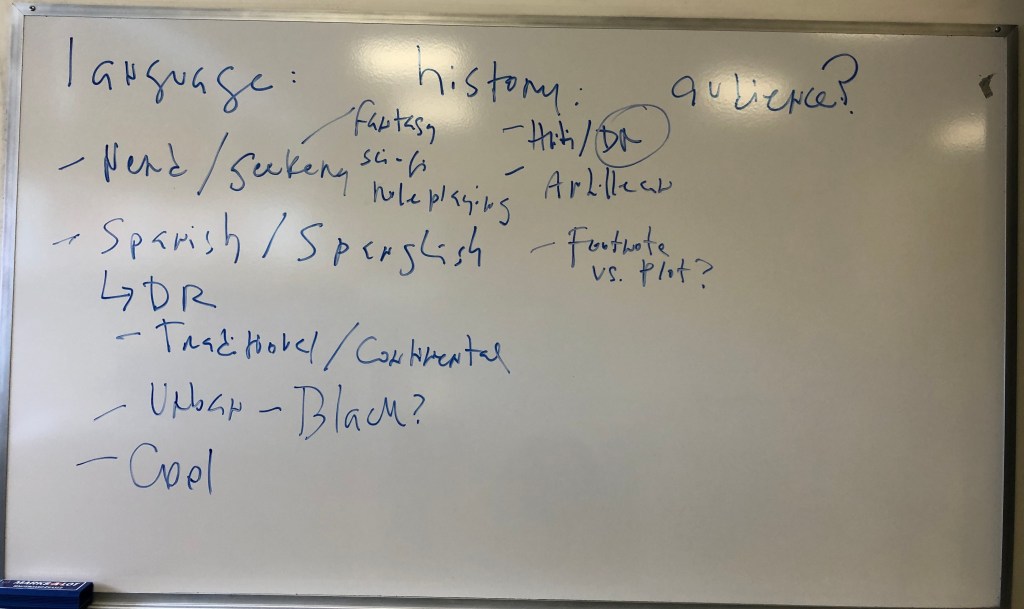

As with most texts, we began our discussion of Oscar Wao visually laying-out the major themes and concerns in the text:

Our introductory class period was mostly spent close reading the epigraphs of the novel, the first from Marvel’s Fantastic Four:

Of what import are brief, nameless lives…to Galactus?”

Fantastic Four

Stan Lee and Jack Kirby

(Vol. I, No. 49, April 1966)

The second is an excerpt from Derek Walcott’s poem, “Schooner Flight”:

Christ have mercy on all sleeping things!

From that dog rotting down Wrightson Road

to when I was a dog on these streets;

if loving these island must be my load,

out of corruption my soul takes wings,

But they had started to poison my soul

with their big house, big car, big-time bohbohl,

coolie, nigger, Syrian, and French Creole,

so I leave it for them and their carnival—

I taking a sea-bath, I gone down the road.

I have known these islands from Monos to Nassau,

a rusty head sailor with sea-green eyes

that they nickname Shabine, the patois for

any red nigger, and I, Shabine, saw

when these slums of empire was paradise.

I’m just a red nigger who love the sea,

I had a sound colonial education,

I have Dutch, nigger, and English in me,

and either I’m nobody, or I’m a nation.

This led us to a discussion of Galactus, his role in the comic book, and how these epigraph might be related to the novel’s title. A cosmic entity who consumes planets in order to sustain life force, Galactus elicits notions of immense force and power. Yet students smartly observed how the novel’s title introduces Oscar as “brief” yet “wondrous,” a word that connotes extra-ordinaryness and otherworldly-ness that perhaps could combat Galactus’ presence. The epigraph from The Fantastic Four also introduces readers to ongoing conversations surrounding the study of popular culture and its relation to notions of “high art.” I pointed students to the careful attention to detail the text lends to this reference, citing not only the comic book’s authors, but also volume number, issue number, and precise date of release (month, day, and year). I asked students to consider this archival minutia––geekery if I’ve ever seen any––in relation to how Walcott’s poem excerpt is referenced, i.e.: without the same citational details of the previous epigraph. In effect, the discrepancies here point readers to understand science fiction, popular culture, and fantasy references to be of more importance in the novel (for more, you can hear Díaz speak about this in the New York Public Library podcast). Although I agree with Díaz that an important secondary or tertiary narrative can be found within these references, the “high” literary details such as the Noble Laureate’s poetry, allusions to Joseph Conrad (“The beauty! The beauty!”), and references to canonical authors are significant for this text and our understanding of Yunior as a burgeoning creative writer. As our discussion of Oscar Wao proceeded, I attempted to place the novel within other literary movements, most importantly postmodern pastiche and the post-9/11 novel.

Notions of uncertainty and cataclysmic terror open the novel, and we spent most of this first class period discussing the importance of fukú americanus as a foundational structure for our reading practices and understanding of the novel’s characters, diasporic history, and potentials for redemption. I asked students to consider the following questions as they continued their reading of the book, keeping fukú as an essential keyword in the plot: How does fukú structure the novel? How does this term introduce us to Antillean history and the potentials for Dominicans in the DR and its diaspora? How does this term teach us to the read everything that follows?

Like the texts we read before this one, our discussion centered on the notion of haunting and the possibility of escaping the horrors of history and trauma-as-lineage. As with We the Animals, our conversation about Oscar Wao addressed the human body, Oscar’s obesity and Belicia’s hypersexual representations. I posited that throughout the novel the female body is presented as a world-destroying presence, a harbinger of (male) apocalypse. For example, the novel describes the Gangster’s desire for Belicia as follows:

I mean, what straing middle-aged brother has not attempted to regenerate himself throughthe alchemy of young pussy. And if what she often said to her daughter was true, Beli had some of the finest pussy around. The sexy isthmus of her waist alone could have launched a thousand yolas, and while the upper-class boys might have had their issues with her, the Gangster was a man of the world, had fucked more prietas than you could count. He didn’t care about that shit. What he wanted was to suck Beli’s enormous breasts, to fuck her pussy until it was mango-juice swamp, to spoil her senseless so that Cuba and his failure there disappeared. (123-124)

In its depiction of Belicia, the novel not only sexually objectifies the Afro-Caribbean female body but also transforms her into the earthy arena on which past historical events such as the Cuban Revolution are explored. The novel considers the hemispheric turbulence caused by Cuban Revolution through its individual effects and its repercussions on the female body, staging sexual intercourse as an extension of dictatorial violence. The Gangster’s future after the Revolution appears “cloudy” (123), and the act of “fuck[ing]” Belicia enables the transformation of her vagina into a stereotypically natural (and tropical) space of danger, stagnation, and death that erases entire political movements. There is much more to say about this passage, but this is just a brief close reading I performed for my students to demonstrate how to “mine the text for meaning” (a phrase I use to talk about analyzing texts).

In effect, there is so much to say about this novel. However, I want to conclude this post about teaching Oscar Wao by commenting on our discussion on the novel’s silences and those things left unsaid (something that returned us again to Morrison’s work). Throughout our conversation we also talked about Yunior’s reliability as a narrator, the novel’s multilinguality and code-switching (i.e.: who is this novel written for?), the sexual politics and misogyny that runs throughout the text, and the footnotes as presenting a counter-narrative to the Oscar and Yunior’s story.

There are many silences in The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao, as can be seen in the various references to “página en blanco” (blank page/s) (78, 90, 119). As with the unknowable words of the mysterious Mongoose that rescues Beli from the cane fields––“_____ _____ _____” (301)—and the words Yunior cannot say to Lola (represented textually identical to the Mongoose’s)—“and I’d finally try to say the words that could have saved us. _____ _____ _____” (327)—the de León family history and the nation’s past is unrecoverable. Abelard, Oscar’s grandfather is rumored to have written a book about the horrors of Trujillo and the cataclysmic past of the Dominican Republic. However, this book, like Oscar’s final letter is never read/found. Throughout our discussion on the novel’s silences, I presented an argument to my students about the possibilities of representing the horrors of Caribbean history and its haunting in the present, and whether the novel can indeed act as a “zafa.” Like Oscar’s excessive physical description and Belicia’s hyper-sexuality, I argued to my students that the novel demonstrates the impossibility of depicting the horrors of history through narrative language. The text reverts to multiple beginnings and endings, excessive descriptions of violence (physical and emotional), multiple references to popular culture and “high art,” and those things left unsaid in order to attempt to depict the haunting of Caribbean violence, without completely being able to do so.

Like Yunior, I am finding it difficult to end my writing about this story. I leave you with this reading by Díaz from the novel. He is a wonderful public speaker and reader of his own work, and I showed my students this clip to demonstrate the power of his narrative voice:

There is so much scholarship on Díaz and Oscar Wao. The following are so of my favorite articles and chapters about this work:

Hanna, Monica. “‘Reassembling the Fragments’: Battling Historiographies, Caribbean Discourse, and Nerd Genres in Junot Díaz’s The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao.” Callaloo32, no. 2 (2010): 498–520.

Machado Sáez, Elena. “Dictating Diaspora: Gendering Postcolonial Violence in Junot Díaz and Edwidge Danticat.” Market Aesthetics: The Purchase of the Past in Caribbean Diasporic Fiction, University of Virginia Press, 2015, pp. 154–96.

Miller, T.S. “Preternatural Narration and the Lens of Genre Fiction in Junot Díaz’s The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao.” Science Fiction Studies 38, no. 1 (2011): 92–114.

Saldívar, José David. “Conjectures on ‘Americanity’ and Junot Díaz’s ‘Fuku Americanus’ in The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao.” The Global South 5, no. 1 (Spring 2011): 120–36.

Vargas, Jennifer Harford. “Dictating a Zafa: The Power of Narrative Form in Junot Díaz’s The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao.” MELUS: Multi-Ethnic Literature of the U.S. 39, no. 3 (2014): 8–30.

Further Díaz reading:

“Watching Spider-Man in Santo Domingo,” The New Yorker, November 20, 2017.

“Under President Trump, Radical Hope is Our Best Weapon,” The New Yorker, November 21, 2016

“MFA vs. POC,” The New Yorker, April 30, 2014

“Loving Ray Bradbury,” The New Yorker, June 6, 2012